(Translated from the original Tibetan) July 2, 2025 Source: The Office of His Holiness...

By Tibet Press July 2, 2025 | Dharamshala, India The United States has restored...

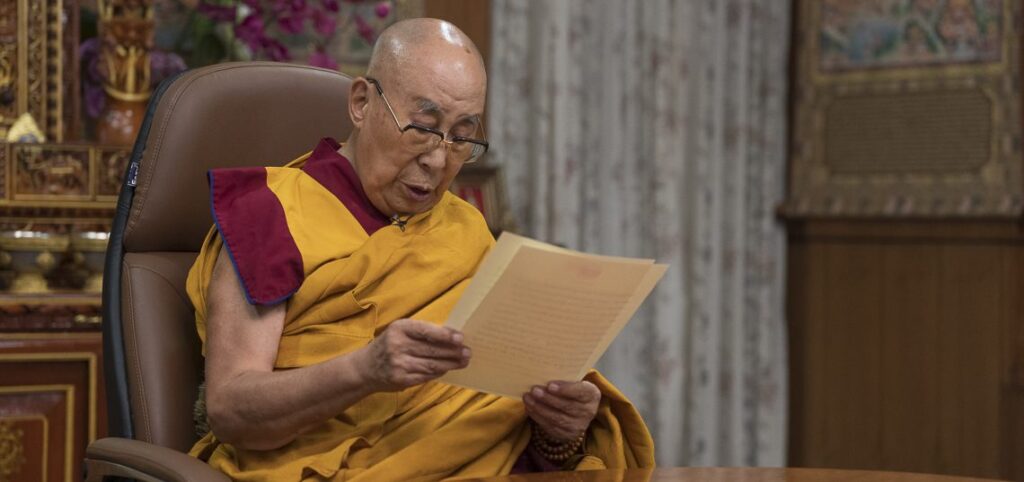

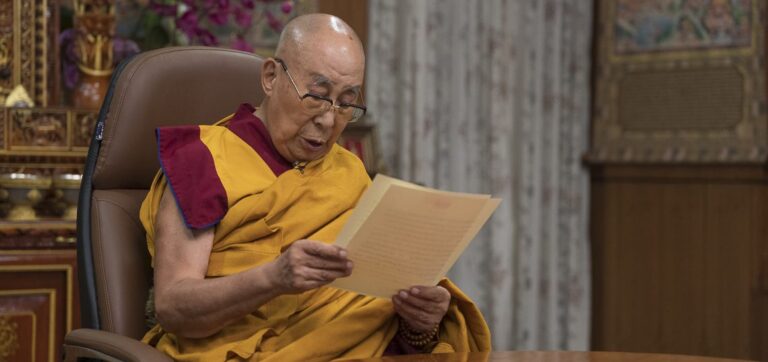

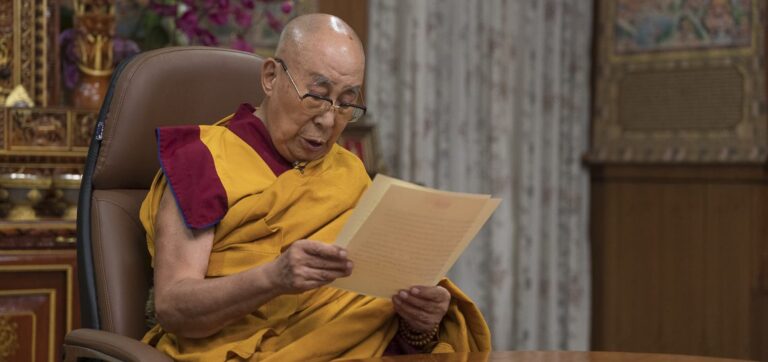

By Tahir Imin UyghurianJuly 2, 2025 In a historic and clarifying statement, His Holiness...

Tibet Press is seeking passionate writers, journalists, experts, and activists to contribute news reports,...

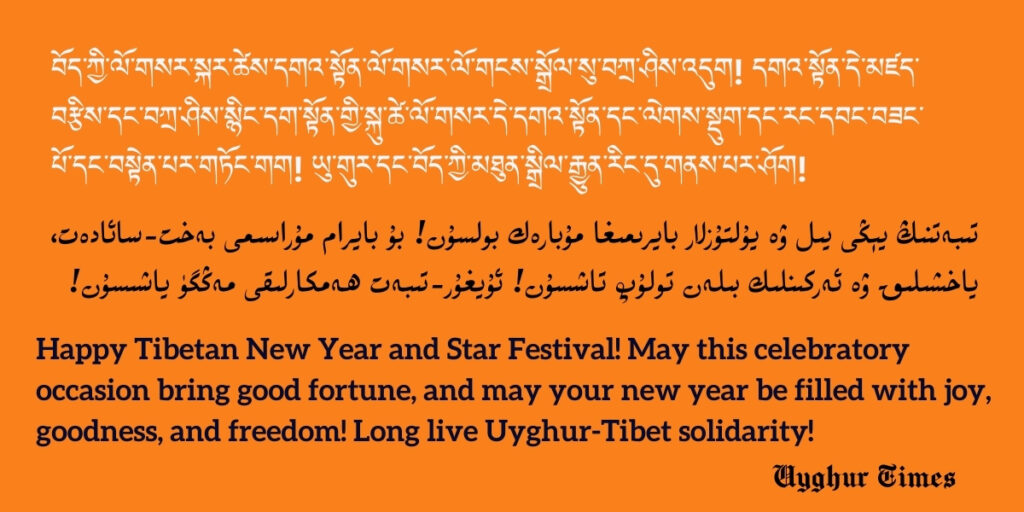

Tibetan New Year, known as Losar, is the most significant and widely celebrated festival...

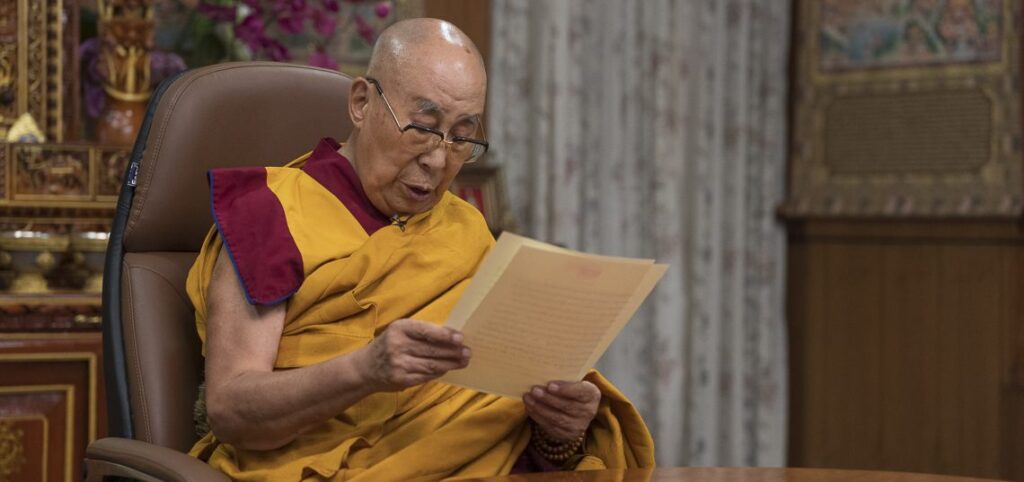

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is the spiritual leader of Tibet....

The source: Tibet.net TIBET, the Roof of the World, is a vast country –...

BackgroundTibet Press (TibetPress.com) is an independent media platform dedicated to reporting on Tibet’s history,...

Tibet Press is dedicated to providing independent, in-depth coverage of Tibet’s history, culture, human...

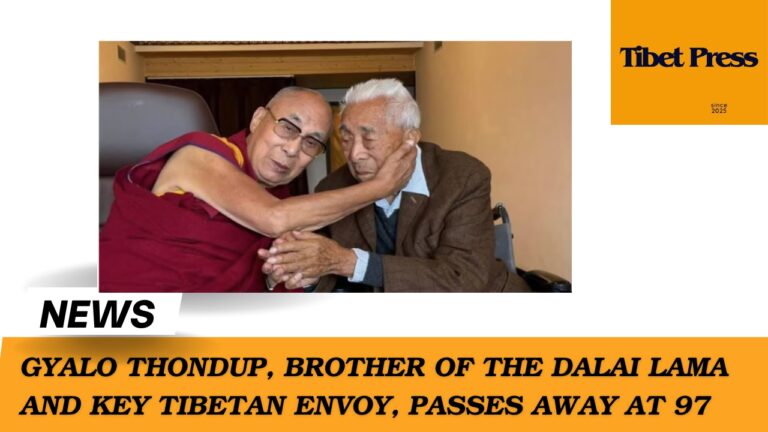

By Tibet Press Staff Gyalo Thondup, the elder brother of His Holiness the 14th...